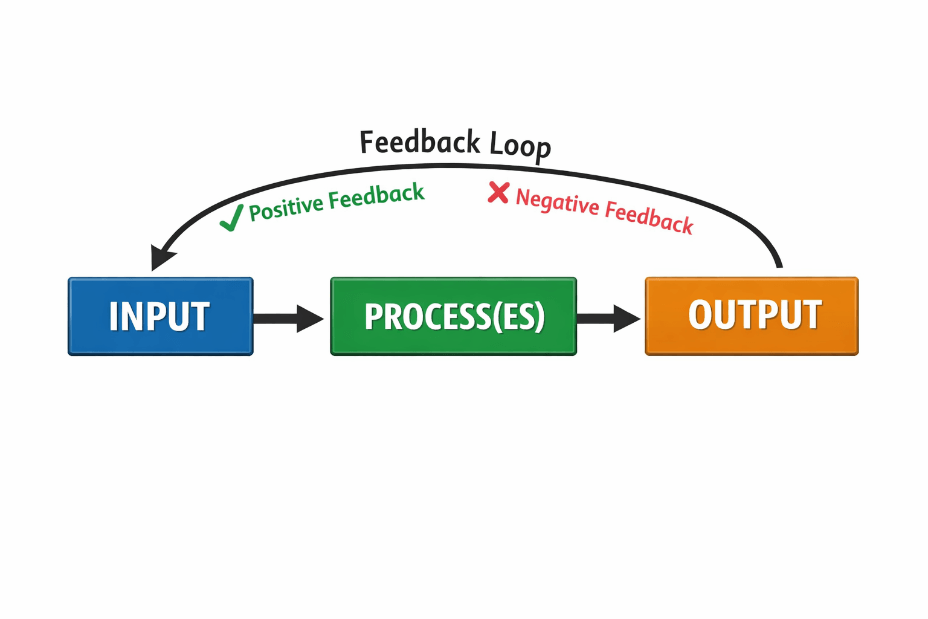

Welcome to the first AVP blog in quite a while! As AVP experienced significant growth in 2025, this blog fell to the wayside. As a fun way to bring the AVP blog back, I am starting a series of posts connecting veterinary business challenges to clinical analogies. I have found throughout my transition from working full time as a practicing clinician, to being on the “business” side of veterinary medicine, that there are tons of parallels to be made between these two worlds. Biological systems, financial systems, and operational systems generally share a lot of underlying fundamental elements, even if the overlying concepts differ. At a very basic level, there is generally one or more input/output systems that function in simple circuits with feedback loops:

Taking complex systems and breaking them down into a collection of simpler input/output systems and processes is a helpful approach both in clinical practice and in business management.

For the first blog in this series, I’ll be tackling a common and complex aspect of a veterinary hospital’s P&L: Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). COGS refers to the direct cost of the goods and services rendered by the practice, with most of the contribution to COGS in a typical veterinary practice arising from pharmaceutical, laboratory, and medical goods expenses. When discussing P&L impact of COGS, rather than focusing on absolute expense, we commonly discuss it as a percentage of revenue, referred to as COGS%. Benchmarks for “good” COGS% will vary by source, but in general it is recommended for small animal general practices to target 20-25% COGS% or better. Mixed animal practices and large animal practices will commonly (but not always) run higher COGS% than their small animal-exclusive peers due to a lower service:inventory revenue mix.

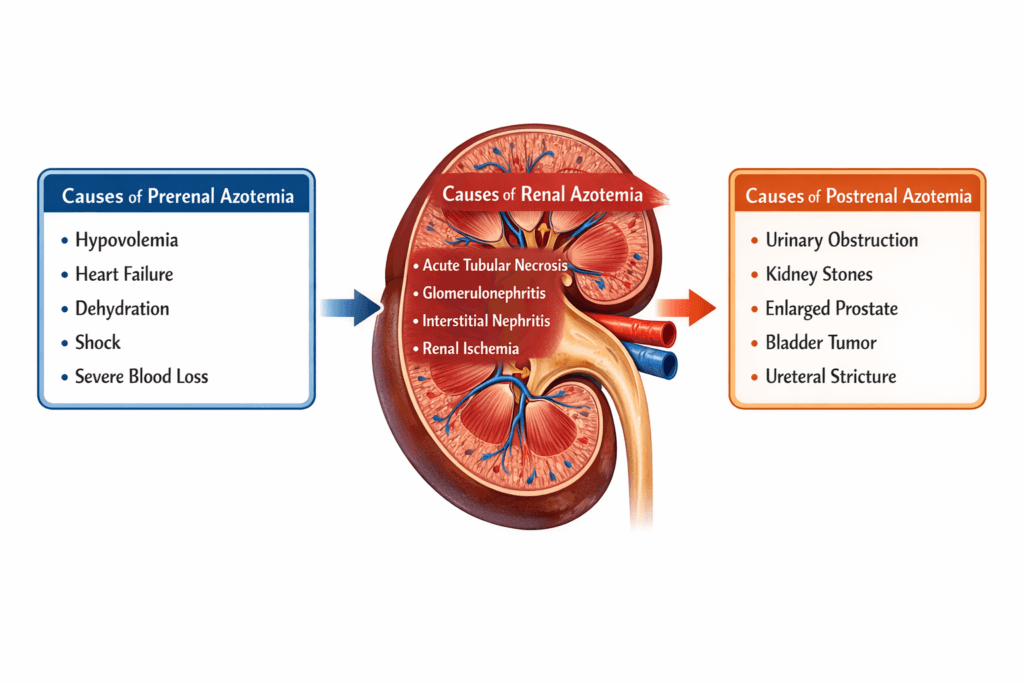

As our clinical analogy, we’ll be looking at azotemia. Azotemia refers to the accumulation of high levels of nitrogen-containing waste products, like urea and creatinine, in the blood, indicating the kidneys aren’t filtering effectively. While in a clinical setting our minds are often drawn to disease of the kidneys as an initial reaction to azotemia, the presence of azotemia is not confirmation of kidney disease by itself and azotemia can result in issues occurring “before” or “after” the kidneys in the process of excreting nitrogenous waste from the body. Thus, causes of azotemia can be grouped into three categories: Prerenal (“before” the kidneys), renal (within the kidneys), and postrenal (after the kidneys).

Image source: ChatGPT

While the pathophysiology of the excretion of nitrogenous waste is quite complex involving several processes and various pathologies that can arise at each step in that process, stepping back to a high level view allows us to simplify and categorize: Nitrogenous waste needs to be delivered to the kidneys (prerenal), successfully filtered from the blood (renal), and then excreted from the body (postrenal).

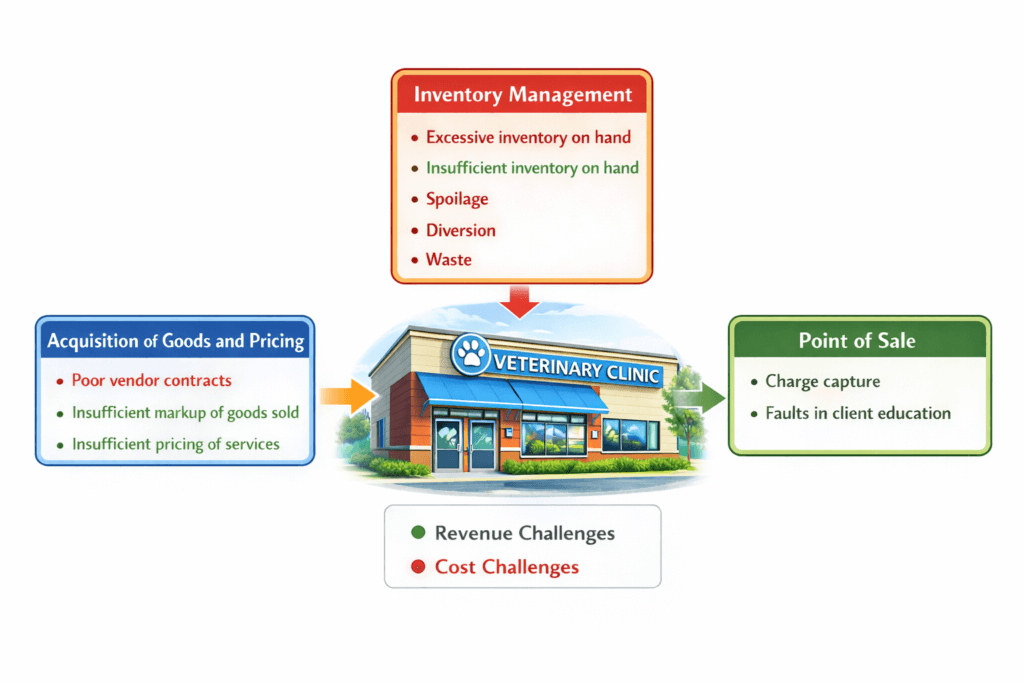

Similarly, goods move through a veterinary clinic through various channels, and many “pathologies” can be applied to each of those processes, but a bird’s eye view of the journey of those products from ordering through to point of sale allows us to create three larger buckets:

- Acquisition of the goods (ordering) and the plan for how those goods will be realized as revenue (pricing)

- Inventory management

- Point of sale

Within those three buckets we can then group “pathologies” within two categories: Revenue challenges and Cost challenges. Just like azotemia represents an accumulation of nitrogenous waste as a relative measure (blood concentration, amount divided by volume), COGS% can be thought of as a “concentration” or fraction, where cost is divided by revenue. Problems arise either when the numerator (cost) is inflated or when the denominator is deflated (revenue).

Image source: ChatGPT

Looking at each of these buckets individually, we see a variety of potential “pathologies” that can manifest as an inflation of COGS% on the Profit & Loss statement (P&L).

Acquisition of Goods and Pricing:

As an analogy to the delivery of nitrogenous waste to the kidneys, to sell goods a clinic must first acquire them and develop a plan for how the inventory and service sales that those goods will drive will be priced. This presents several potential process break points:

- Poor vendor contracts: Unfortunately, not everyone is paying the same amount for the same goods. The quality of vendor contracts can vary greatly. Paying more for goods can lead to cost pressure, especially for “shoppable” goods such as heartworm and flea & tick preventatives where the ability for the clinic to mark up pricing is limited.

- Insufficient markup of goods sold: This is the half of the pricing equation that often comes to mind first for veterinary practice leaders when they think about fixing elevated COGS%. If you’re not marking up your inventory sales enough, creating an insufficient gap between what the clinic paid and the client pays, this will increase COGS% in a very simple and predictable way.

- Insufficient pricing of services: This is the half of the pricing equation that often doesn’t get enough attention when troubleshooting elevated COGS%. COGS% is expressed as the division of cost by ALL revenue, not just inventory sales. That means that any revenue deficiency will drive COGS% up, not just your pricing of the goods themselves. If service revenue is lagging, COGS% is one place where the impact will manifest on the P&L.

Inventory Management:

Just as the kidney filters nitrogenous waste out of the blood and delivers it into urine, the clinic must receive, store, and prepare to sell goods. How goods are handled within the clinic can introduce potential COGS “leaks”. In general, clinics should aspire for a “just in time” ordering strategy to ensure that the clinic does not miss revenue opportunities due to not having products on hand that a client is willing to buy, but also does not result in excessive stock of inventory that can promote spoilage, diversion, and waste. Accomplishing “just in time” ordering is much easier said than done, but is an investment of time and attention of clinic leadership that pays dividends. COGS is typically the second largest expense on the P&L only ranking behind labor expenses at most veterinary clinics, so managing COGS% can yield significant benefit for the practice’s bottom line. Looking at potential faults in inventory management:

- Excessive inventory on hand: It is a common saying that “inventory likes to grow legs”. Failing to turn inventory at a sufficient rate creates opportunities for that inventory to end up somewhere other than realizing revenue, whether that is spoilage, diversion, or wasteful use.

- Insufficient inventory on hand: Not having enough inventory is a paradoxical driver of COGS% elevation. Starving the practice of inventory, particularly inventory that drives services and/or has wider markup (interventional medications, etc.) means starving the practice of revenue opportunities, reducing the denominator in the cost/revenue equation.

- Spoilage: Driven by having too much inventory on hand or stocking low turn or redundant inventory drives spoilage. Most inventory within a veterinary practice carries an expiration date, which creates an urgency to ensure inventory is sold or utilized prior to spoiling. Spoilage, like charge capture, drives a dollar-for-dollar bottom line impact. Simply put, if you spend money on inventory that never drives revenue, that is a direct subtraction from the clinic’s profit. This makes spoilage management crucial.

- Diversion: This is an uncomfortable topic, as most practice leaders don’t want to consider the possibility that their trusted team members are stealing from the clinic, but unfortunately diversion is a common issue at veterinary practices. Most theft is a crime of opportunity, where theft occurs because the thief perceives a minimal chance that the theft will be noticed. This means that even simple deterrents are effective at reducing or eliminating theft, such as avoiding having excessive inventory on hand, performing inventory counts more frequently, and installing basic security measures such as security cameras in pharmacy areas and ensuring high-risk diversion items (high value, easy resale, small size) are appropriately secured.

- Waste: If you can get the job done with one pack of suture, gauze, cast padding, etc. and you consistently use three instead, wasteful usage will eventually add up. It is a fine balance, as you obviously don’t want to restrict usage in a way that will negatively impact patient care and/or operational efficiency, but helping team members understand how wasteful usage creates financial challenges for the practice will pay dividends as waste functions similarly to spoilage and charge capture with a dollar-for-dollar bottom line impact. Keeping excessive inventory on hand can create psychological bias towards waste, as having drawers brimming with something creates a perception of “plenty”, where the item in question is not precious.

Point of Sale:

Like the final step of eliminating nitrogenous waste from the body, excretion, ensuring that the goods and services rendered are charged for is the final and impactful step in the journey of goods through a veterinary practice. This is also a very common fault point for veterinary practices, making elevated COGS% likewise a common issue:

- Charge capture: Charge capture describes the failure of goods or services rendered to end up on the final invoice paid by clients. Charge capture failure drives direct dollar-for-dollar reduction from profit, unlike other forms of unrealized revenue, as costs have already been incurred by the clinic for the services rendered. Every veterinary clinic has some degree of charge capture challenges, deriving either from process failures (intended to charge, but did not) to discretionary (services were rendered, but for some reason the team elected not to charge). A degree of discretionary discounting is normal and appropriate to ensure the team has options available when approaching challenging situations, but there needs to be a clear and mutually agreed approach to how this discretionary discounting occurs within the team and clinic leadership to ensure that the amount is controlled and that fees are set accordingly to recoup this lost revenue elsewhere.

- Faults in client education: Most veterinary clients are well-intentioned and want to make the right decisions for their pet’s health. While true financial barriers exist for many clients, especially in situations where the costs incurred were not expected (i.e. illness or injury), many declined services in veterinary practice settings occur because a client does not feel that the incremental cost being provided is being matched with equivalent value. This is where client education becomes a critical part of ensuring that clients understand the “why” behind every line item on a treatment plan being presented to them. Rather than just being “costs”, education communicates these items as “value”. This is not only important for realizing more revenue for the practice, but a critical aspect of providing excellent clinical care to our patients. Ultimately, we can only perform as much care as clients are willing to approve and pay for, so we cannot be good clinicians without also being good educators.

When you hear hoofbeats, think ‘horse’ instead of ‘zebra’:

This is a popular phrase in medical practice, meant to drive home the point that common diseases happen commonly. It is important to keep uncommon diseases in mind as a possibility when presented with a case, particularly if the fact pattern doesn’t match well with common diseases, but it is most efficient to focus on ruling out common causes first before looking for “zebras”. The same is true for trying to diagnose COGS% challenges. Veterinary practice leaders will often focus excessively on inventory management when trying to solve COGS% challenges, sometimes leading to inventory level austerity that ends up making the problem worse instead of better (see above). In practice, COGS% challenges are more commonly driven by “common diseases” of veterinary practices: Charge capture, insufficient pricing, and service mix (insufficient client education). Tackling waste, spoilage, and diversion are an important part of running a successful veterinary practice, but stubborn COGS% more often originate from faults in realizing revenue rather than truly excessive underlying costs, especially at clinics that are already generally already following “best practices” around inventory management.

If you are interested in learning more about various topics in veterinary practice management and the intersection of clinical and business topics, please check out the other blog posts on our website at www.yourvetpartner.com and sign up for our mailing list to be notified when new blog posts arrive. You can also follow me on LinkedIn here to access shorter-form topics that I periodically post on my feed. If you are interested in learning more about partnering your practice with AVP, please email me at bill@yourvetpartner.com. If you are interested in learning more about joining an AVP partner practice or the AVP Success Center as a team member, a list of open positions can be found at here.

Your vet partner,

Dr. Bill Wagner